Economic Analysis of Production of Sweet Orange in Anantapuramu District of Andhra Pradesh

0 Views

Ch. SHEKHAR*, K. KAREEMULLA, S. RAJESWARI AND B. RAMANA MURTHY

P.G. Scholar, Department of Agricultural Economics, S.V Agricultural College, ANGRAU, Tirupati

ABSTRACT

The present study aims at examining the economic viability of sweet orange in Anantapuramu district of Andhra Pradesh. Forty sweet orange farmers constituted the sample for the study. Data collected from primary sources have been analyzed with the set objectives using appropriate techniques. Average establishment cost was worked out to be ` 326479 per hectare of sweet orange. The gross returns per hectare of sweet orange has been worked out to be ` 1479465 during 5 to 10 years age, ` 4001250 (11 to 20 years age) and ` 3072630 (21 to 30 years age). The farmers were receiving a net income of ` 22487.66 through inter crops during pre bearing period. Even after taking the returns from intercrops, the farmer has to bear a loss of ` 303991.34 during pre bearing period. The net returns obtained were ` 1024650 during 5 to 10 years age to ` 3237878 (11 to 20 years) and

` 2294163 ( 21 to 30 years age). The net present value, benefit-cost ratio and internal rate of return were ` 2,192, 536.87, 3.04 and

23.6 per cent. The findings of the study show that sweet orange was a profitable and promising enterprise for the driest district of Andhra Pradesh state. There was a greater scope for setting up of processing industry for sweet orange which helps to the growers to realize better price for their produce, which also generates employment. Given the fruit product diversity, that also spreads in terms of production across seasons, the farmers may be encouraged to form producer’s societies on a co-operative basis to market their produce and also realize higher value for their produce.

KEYWORDS: Sweet orange, Establishment costs, Discounted measures and Economic Analysis.

INTRODUCTION

Horticulture sector shows an enormous potential to raise the farmers income, provide livelihood security and earn foreign exchange through exports. India is the second largest Producer of fruits and Vegetables in the world, contributing about 9.3 per cent share of total world production. In 2020-21, the production of horticultural crops recorded an enormous production of 326.6 million tones (MT) which is more than the total food grain production (Abhishek et al., 2021). Further there was a change in the consumer preferences across all expenditure classes towards fruits and vegetables (Sarma et al., 2018). This increasing trend in production of horticultural crops was also observed in sweet orange in India, where the area under sweet orange increased from 157 to 191 thousand hectares from 2010-11 to 2019-20. India had made fairly good progress in sweet orange production for the same period with increased production from 1316 thousand tones to 3483 thousand tones. The yield of sweet orange has raised from 8.4 to

18.23 tonnes per ha during the above period. In India sweet orange is majorly grown in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Telangana, Maharashtra and Gujarat. In the year 2018, the sweet orange production in the state of Andhra Pradesh was 2003.11 thousand tonnes (Anonymous, 2020). Anantapuramu district ranked first both in area (31,693.45 ha) and production (34.83 lakh tonnes) of sweet orange in Andhra Pradesh. Sweet orange contains large amounts of potassium, which might help to prevent high blood pressure and stroke. The fruit and juice also contain large amounts of a chemical called citrate, which might help to prevent kidney stones. Citrate tends to bind with calcium before it can form a stone. In this background the present study was focused on economic analysis of production of sweet orange in Anantapuram district of Andhra Pradesh.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Multistage purposive random sampling method was adopted to select the ultimate sample for the study. Anantapuramu district was purposively selected for the present study as it has the highest area under sweet orange in Andhra Pradesh. Based on acreage under sweet orange. top two mandals i.e., Tadipatri and Mudigubba were selected for the study. Using the same criteria top two villages from each mandal were selected. From each village 10 sweet orange farmers were selected randomly, thus the total sample for the study was 40. Primary data was collected for the agricultural year 2020-21 through personal interview with the help of a well structured schedule. To know the costs and returns simple arithmetical tools were employed and the financial feasibility of sweet orange orchards was analysed using discounted measures like NPW (Net Present Worth), B-C ratio (Benefit Cost ratio) and IRR (Internal rate of Return). Bhat et al. (2011) also employed these discounted measures to study the economic appraisal of kinnow production under north-western Himalayan region of Jammu.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Socio-economic profile of selected orchardists

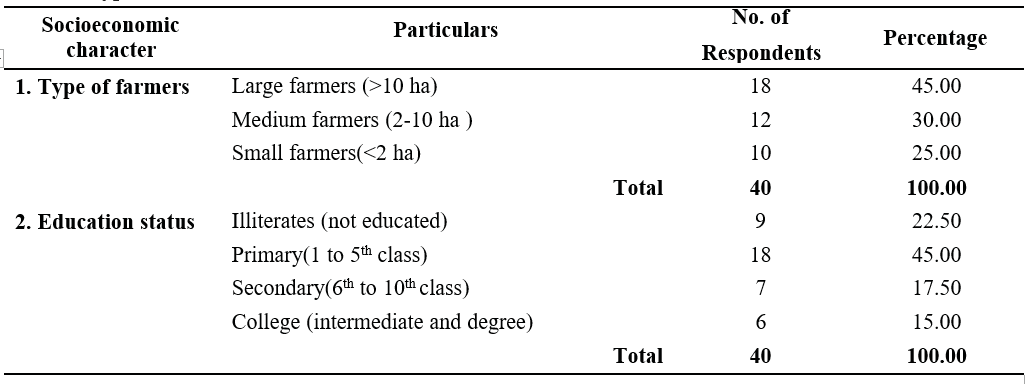

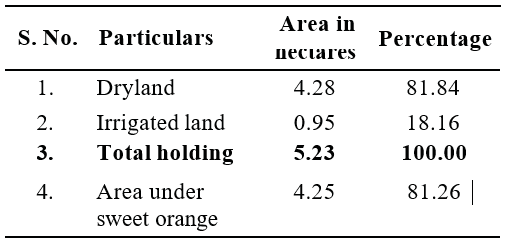

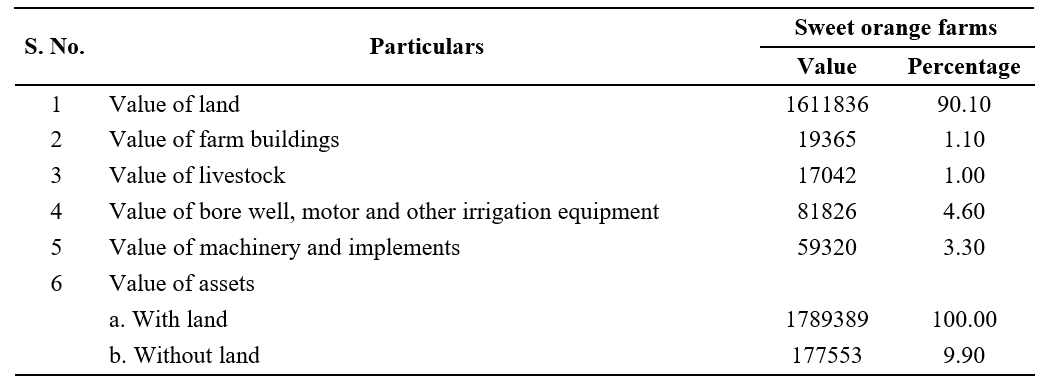

This provides a comprehensive understanding of the composition of type of farmers, education status, average size of farm holding and asset structure of the selected farm respondents. The results presented in Table 1 revealed that 45.00 per cent of the sample respondents were large farmers, 30.00 per cent of them were medium farmers and 25.00 per cent were small farmers. Majority of the farmers (45.00%) had their primary education, 22.50 per cent were illiterates, 17.50 per cent had secondary education and 15.00 per cent studied up to college level. The land holding particulars of the respondents presented in Table 2 disclosed that the average size of the land holding of the sample respondents was 5.23 ha and of the total holding, 81.84 per cent constituted the dry land and the remaining was irrigated land (18.16%). Further 81.26 per cent of the total holding of the respondents was under sweet orange cultivation. The income earned by the farmers and the risk bearing ability of the farmers largely depends on the value of the assets owned by them. From the results it was found that land value constituted a major item of the total assets (90.10%). The value of other assets like farm buildings, live stock, bore well, motor and other irrigation equipment and machinery and implements constitutes only 9.90 per cent (Table 3) of the total value of the assets.

Resources and resource services utilization on sweet orange orchards

Production of sweet orange requires material inputs viz., planting material, Farm Yard Manure, plant

Table 1. Type of Farmers and educational status in the Selected Orchardists

Table 2. Average size of land holding of the sweet orange orchardists

protection chemicals etc., as well as resource services like human labour, machinery etc. The value of these resources and resource services forms cost structure of sweet orange production. On an average the sample farmers were maintaining a plant population of 220 grafts per hectare. The quantity of manures varied from 16 tonnes per hectare during the establishment period to 18.6 tonnes per hectare during 5 to 10 years, 37 tonnes per hectare in the 11 to 20 years and 28 tonnes per hectare in the 21 to 30 years age of the orchard. The use of N, P, K nutrients in the form of DAP, single super phosphate and murate of potash for sweet orange orchard stood at 193, 158 and 277 kg per hectare per annum during 0 to 4 years age, 290, 180 and 290 kg per hectare from 5 to 10 years, 712, 348 and 402 kg per hectare from 11 to 20 years and 804, 514 and 522 kg per hectare during 21 to 30 years age of orchards respectively. There was an increase in the application of N, P, K from 11th year onwards on commencing of economic yields. Plant protection chemicals were applied in the form of dusts (sulphur, carbendazem + mancozeb) and liquids (dichlorvous, imadachloprid). The quantity of dusts and liquids applied to control pests and disease were 20 kg and 14 lit per hectare per annum during 0 to 4 years age,

Table 3. Asset Structure of the orchardists of sweet orange farms

Table 4. Material input utilization on sweet orange orchard per hectare of an average farmer

25 kg and 32 lit from 5 to 10 years age, 42 kg and 45 lit from 11 to 20 years age and 58 kg and 52 lit per hectare from 21 to 30 years age. It was clearly inferred that the quantity of plant protection chemicals increased with increase in the age of the orchard.

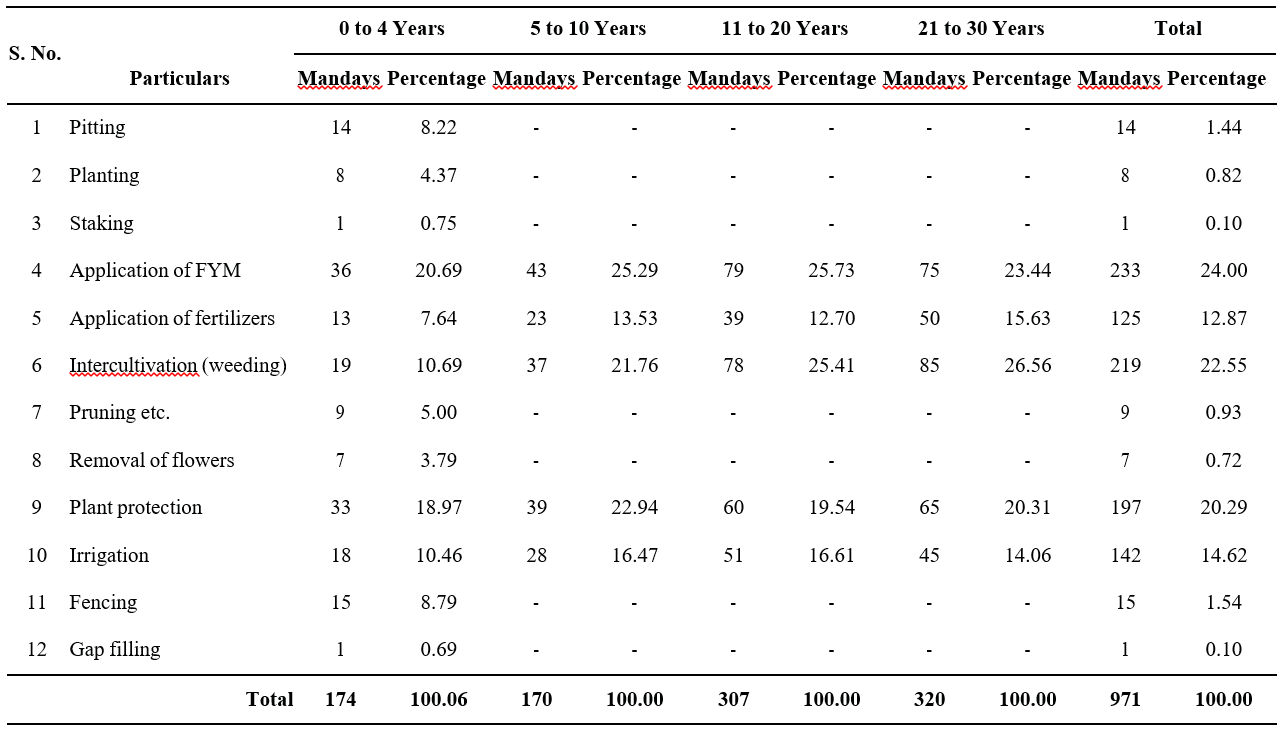

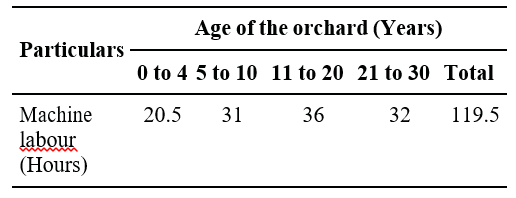

The total labour requirement for the cultivation of sweet orange during its economic life period was 971 man days ha-1 (Table 5). It was noted that major labour consuming operations were application of FYM, inter cultivation, application of plant protection chemicals, irrigation and application of fertilizers. Pruning and removal of flowers operations were undertaken only during the establishment period only, Hence, these operations required less labour about 16 mandays ha-1 in sweet orange orchards. The operations which are performed only once in the life period of orchard were pitting, planting, staking, fencing and gap filling took still lesser share of labour. Majority of the farmers in the study area go for dispose of the standing crop to the pre harvest contractor. The farmers believe that it is a safety measure against the fluctuations in prices of sweet orange. Hence there was no human labour utilization for harvesting operation in the study area. It is evident from Table 6 that the machine power utilized by sweet orange farmers was 199.5 hrs per hectare during the entire economic life of sweet orange. The machine power was used for operations like land preparation, inter- cultivation and sprayings.

Costs and returns from sweet orange orchards

Sweet orange was a perennial commercial crop can be cultivated economically for about 30 years. It takes four years to establish and starts yielding from fifth year onwards. Therefore, the costs incurred in establishing the orchard during the pre-bearing period at current prices of inputs and input services were considered as

Table 5. Human labour utilization per hectare of sweet orange orchard

Table 6. Machine labour utilization per hectare of sweet orange orchard

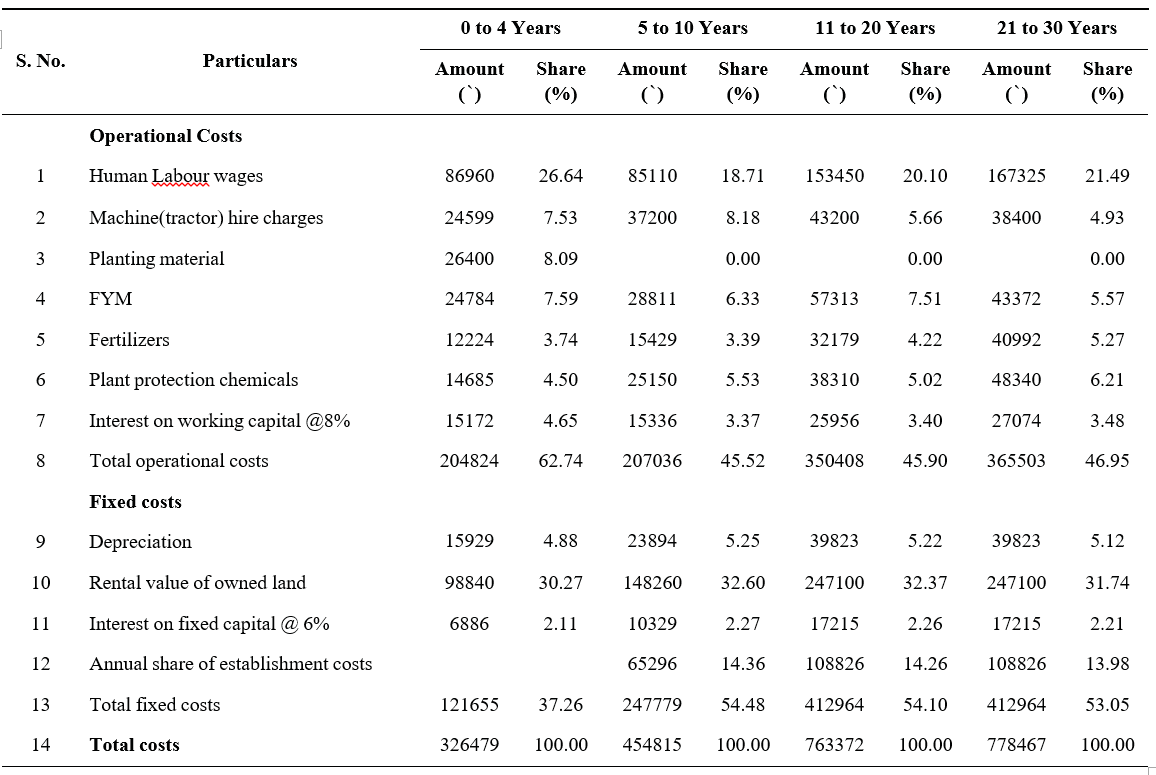

establishment costs. The establishment costs include the expenditure on land preparation, pitting, laying of irrigation channels, fencing, plant material, planting, pruning, removal of flowers and other subsequent operations in nurturing the orchard together with fixed costs. Results presented in Table 7, indicated that the total establishment cost of sweet orange was ` 326479 per hectare. The highest cost item of expenditure was rental value of owned land which was estimated to ` 98840 per hectare, that constitute 30.27 per cent followed by wages to human labour ` 86960 per hectare contributing

26.64 per cent, planting material ` 26400 (8.09%), Farm Yard Manure ` 24784 (7.59%), Machine labour

` 24599 (7.53%). Pokharkar et al. (2016) reported similar observation in their study on economics of production of Guava in western Maharashtra. Annual maintenance costs included the costs incurred to maintain the orchard from 5th year onwards up to the economic life period of the orchard. It is clear from the results that the annual maintenance cost per hectare increased with the increase in the age of the orchard. This is because of higher expenses incurred on various inputs and input services. This increase may be attributed to the direct relationship between the input requirement and age of the plant. The annual maintenance cost ranges from ` 207036 during 5 to 10 years age to ` 350408 during 11 to 20 years and ` 365503 during 21 to 30 years age. Similar results were also reported by Sharma et al. (2006).

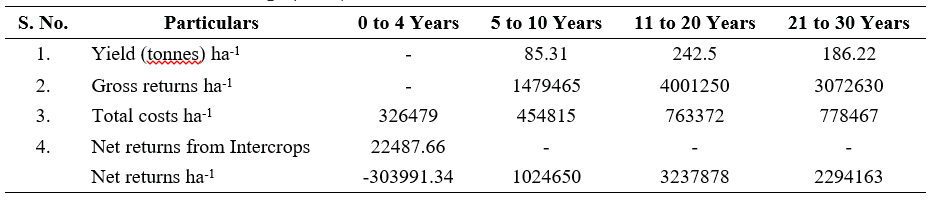

Data presented in Table 8 indicates the costs and returns per hectare of sweet orange orchard at different ages. From the results it was observed that there was no production of sweet orange up to the age of four years, economic yields were obtained only from five years of age. The per hectare production of sweet orange starts increasing gradually from nearly 85.31 tonnes per hectare during 5 to 10 years age to 242.5 tonnes per hectare for 11 to 20 years age and 186.22 hectares for 21 to 30 years age. The gross returns from sweet orange were worked out to be ` 1479465 during 5 to 10 years age, ` 4001250

(11 to 20 years age) and ` 3072630 (21 to 30 years age). After deducting the operational costs along with fixed costs like depreciation, rental value of owned land,

Even after taking the returns from intercrops, the farmer has to bear a loss of ` 303991.34 during pre bearing period. During the fifth year onwards the net returns becomes positive. The net returns were worked out to be

` 1024650 during 5 to 10 yeas age to ` 3237878 (11 to 20 years) and ` 2294163 during 21 to 30 years age.

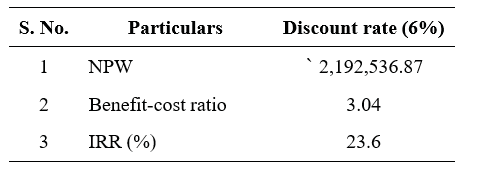

Economic feasibility of sweet orange orchard

In the present study, the costs and returns had been discounted at 6 per cent to estimate the present worth of future returns. The net present value, benefit-cost ratio and internal rate of return for sweet orange orchards were worked out and presented in Table 9. The overall NPV of sweet orange orchard on per hectare at 6 per cent discount rate is found to be ` 2,192,536.87. The formal selection criterion of NPV is to accept all the projects with positive values. Applying this principle, net present value of sweet orange orchard clearly indicates its financial reliability in the study area. The decision in the B-C ratio framework is to select the projects where the ratio is more than one. In the overall farms B-C ratio has been estimated as 3.04 at 6 per cent discount rate which satisfies the rule indicating the worthiness of investment on sweet orange orchard. Similar findings were also observed by Parameshwar et al. (2018) in their study on sweet orange. The benefit-cost ratio indicates expected returns for each rupee of investment in sweet orange orchard. Thus, it can be concluded that investment in sweet orange orchard is economically viable and financially feasible in the area under study. The formal selection criterion of IRR is to accept the projects with IRR more than the opportunity cost of capital. The internal rate of return of the overall farms has been estimated as 23.6 per cent. The IRR represents the maximum rate of interest at which the growers can borrow from lending agencies and invest on sweet orange orchard. Since IRR is more than the opportunity cost of capital it clearly indicates that investment on sweet orange orchard is a financially sound and economically viable proposition in the study area.

In the light of above discussion, it may be concluded that even though the establishment cost of sweet orange is very high yet it is an economically viable enterprise.

Table 7. Cost structure of sweet orange orchard

Table 8. Returns of sweet orange (` ha-1)

Table 9. Estimates of economic viability of sweet orange orchards

Per hectare establishment cost was worked out to be ` 326479. The annual maintenance cost ranges from ` 207036 during 5 to 10 years age to ` 350408 (11 to 20 years) and ` 365503 (21 to 30 years age). The net returns were worked out to be ` 1024650 during 5 to 10 yeas age to ` 3237878 (11 to 20 years) and ` 2294163 (21 to 30 years age). The economic viability of the sweet orange, the net present worth, benefit cost ratio and internal rate of return have been worked out as ` 2192536.87, 3.04 and 23.6 per cent respectively. This indicated that sweet orange was a economically viable enterprise. The results had proven that sweet orange had a vital potential in raising the incomes of the farmer.

POLICY IMPLICATION AND SUGGESTION

- It was found out from the study that the orchardists were unaware of the importance of maintaining optimum plant population, application of nutrients in required doses and hence the agricultural department has to play an important role in educating the farmers in adopting the package of practices.

- Sweet orange cultivation provides a greater scope for setting up of processing industry which in turn helps the growers to realize better price for their produce, which also generates employment.

- Given the fruit product diversity, that also spreads in terms of production across seasons, the farmers may be encouraged to form producer’s societies on a co-operative basis to market their produce and also realize higher value for their produce.

LITERATURE CITED

Abhishek, T., Afroz, S.B and Kumar V. 2021. Market Vulnerabilities and Potential of Horticulture crops in India: With special reference to TOP crops. Indian Journal of Agricultural Marketing. 35(3):1-20.

Anonymous. 2020. Indian horticulture database. National horticulture board, Ministry of agriculture and farmer’s welfare. Government of India, Gurugram. http://www.nhb.gov.in. Accessed on November, 2021.

Bhat, A., Kachroo, J and Kachroo, D. 2011. Economic appraisal of kinnow production and its marketing under north-western Himalayan region of Jammu. Agricultural Economic Research Review. 24(347- 2016-16976): 283-290.

Parameshwar, P., Joshi, P.S and Paithankar, D.H. 2018. Economic analysis of sweet orange varieties in Akola district of Maharashtra, India. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences. 7(4): 1935-1938.

Pokharkar, V.G., Sangle, S.A and Kulkarni, A.R. 2016. Economics of production and marketing of guava in western Maharashtra. International Research Journal of Agricultural Economics and Statistics. 7(2): 234-242.

Raj, K., Nirmal, K., Ashok, D., Dalip, K.B., Kavita and Anil, K.M. 2019. Economic Analysis of Guava (Psidium guajava L.) in Sonepat District of Haryana. Economic Affairs. 64(4): 747-752.

Sarma, A., Borah, T.M and Bezbaruah, M.P. 2018. Efficacy of marketing channels of horticultural crops: A study in Assam. Indian Journal of Agricultural Marketing. 32 (2): 32-46.

Sharma, D.K., Singh, V.K., Khatkar, R.K and Sharma, S. 2006. An economic analysis of mango cultivation in Yamunanagar district of Haryana. Haryana Agricultural University Journal of Research. 36: 105-111.

- Genetic Divergence Studies for Yield and Its Component Traits in Groundnut (Arachis Hypogaea L.)

- Correlation and Path Coefficient Analysis Among Early Clones Of Sugarcane (Saccharum Spp.)

- Character Association and Path Coefficient Analysis in Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.)

- Survey on the Incidence of Sesame Leafhopper and Phyllody in Major Growing Districts of Southern Zone of Andhra Pradesh, India

- Effect of Organic Manures, Chemical and Biofertilizers on Potassium Use Efficiency in Groundnut

- A Study on Growth Pattern of Red Chilli in India and Andhra Pradesh