Constraints Faced by Farm Women in Home and Agricultural Activities and Suggestions to Overcome Them in Telangana State

0 Views

N.A. HINDUJA*, T. LAKSHMI, S.V. PRASAD, V. SUMATHI AND G. MOHAN NAIDU

Department of Agricultural Extension, S.V. Agricultural College, ANGRAU, Tirupati

ABSTRACT

Agriculture is impracticable without the involvement of women. Farm women dominate the work force in agriculture and participate in most of the farm operations. In addition to farm activities, women also involve in copious works at home. Farm women face many constraints in due process of bearing the dual responsibilities at farm and home. In this study, various socio- personal, economic and technological constraints perceived by farm women in Telangana state were analysed and were ranked based on the descending order of the frequencies obtained for each constraint. Study revealed that 23 constraints out of the 34 constraints were ranked as major constraints by more than fifty per cent of farm women respondents in the study area. Seven suggestions were expressed by majority of farm women out of the 10 suggestions given by them to overcome their constraints.

KEYWORDS: Agriculture, Economic constraints, Farm women, Socio-personal constraints, Technological constraints

INTRODUCTION

Farm women are the major contributors to agriculture and allied sectors. They are indispensable to agriculture likewise agriculture is to nation. Farm women contribute equally, also in some cases more than men to farming in addition to obligations they bear at home, such as domestic work and child rearing. Despite their varied tasks at home and on the farm, women face numerous challenges that affect their position and recognition in the house and society. Farm women’s productivity is influenced by the constraints they confront on the farm. Providing a mechanism to minimise or reduce the limits which farm women experience will ensure higher prosperity to nation. Hence, this study was taken up to analyse the constraints faced by the farm women in different spheres of their life.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

An ex-post facto research design was employed in the current investigation. Telangana state was purposively selected. One district each from three agro climatic zones of the state viz., Nizamabad from North Telangana zone, Sangareddy from Central Telangana zone and Nalgonda from South Telangana zone were purposively selected on the basis of highest number of farm women from each agro climatic zone. Four mandals from each district and two villages from each mandal were selected by using simple random sampling procedure and a total of 12 mandals and 24 villages were selected respectively. From each village, ten farm women were selected thus making a total of 240 respondents as the sample of the study. In this study, ‘constraint’ was operationalized as the obstacle perceived by the farm women in various spheres of their lives. A total of 34 constraints were identified and grouped into three categories as ‘socio-personal’, ‘economic’ and ‘technological/on farm’ constraints. Alongside constraints, ‘suggestions’ expressed by the farm women were documented and in this study ‘suggestion’ was operationalized as, ‘the requirements expressed by the farm women in order to fulfil their needs’. The suggestions expressed by the farm women were keenly observed and framed into 10 major suggestions. The field investigation was carried out during the year 2017. The data was collected by administering the structured interview schedule to the farm women and were measured using frequency and percentage. The results were presented in table 1 and table 2 and necessary inferences were drawn.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

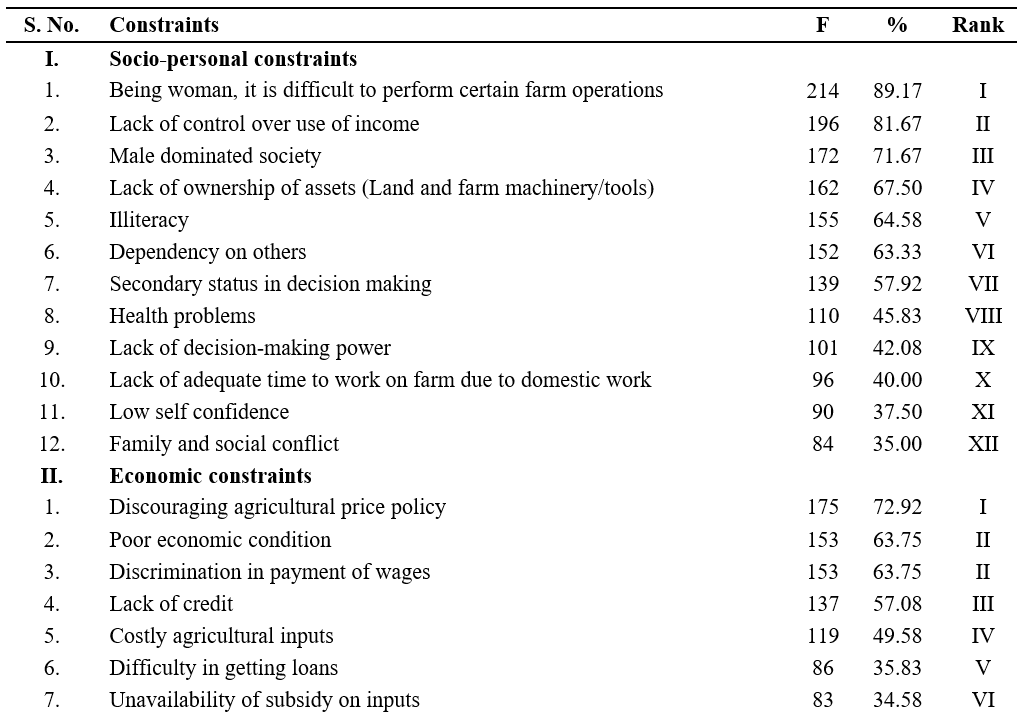

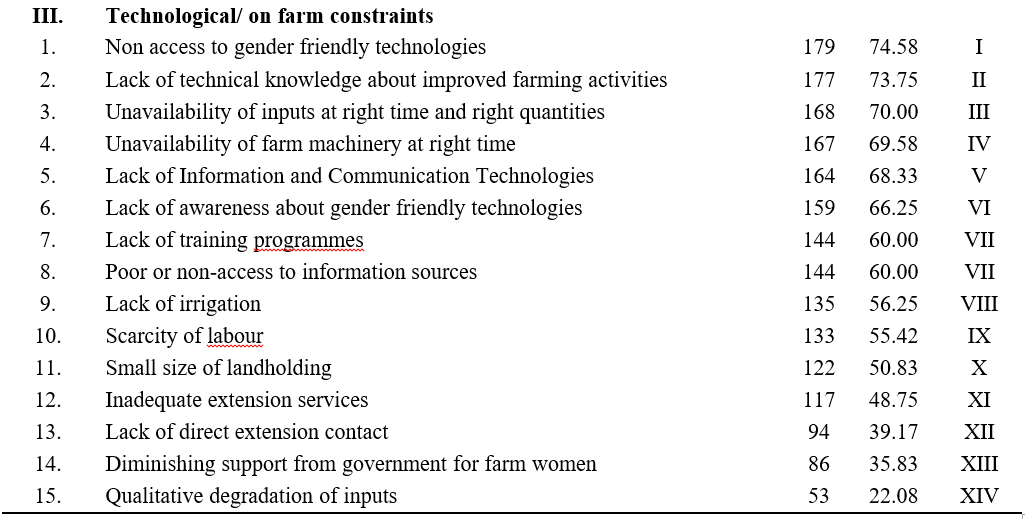

Constraints faced by farm women were classified into three major categories viz., socio-personal, economic and technological/on farm constraints and were presented in Table 1. Major socio-personal constraints faced by farm women were, ‘being woman, it is difficult to perform certain farm operations’ (89.17%), ‘lack of control over use of income’ (81.67%), ‘male dominated society’ (71.67%), ‘lack of ownership of assets (land and farm machinery/tools)’ (67.50%), ‘illiteracy’ (64.58%), ‘dependency on others’ (63.33%) and ‘secondary status in decision making’ (57.92%). Most of the farm women perceived ‘health problems’ (45.83%), ‘lack of decision making power’ (42.08%), ‘lack of adequate time to work on farm due to domestic work’ (40.00%), ‘low self- confidence’ (37.50%) and ‘family and social conflict’ (35.00%) as other socio-personal constraints in their lives.

The economic constraints faced by farm women were, ‘discouraging agricultural price policy’ (72.92%), ‘poor economic condition’ (63.75%), ‘discrimination in payment of wages’ (63.75%), ‘lack of credit’ (57.08%), ‘costly agricultural inputs’ (49.58%), ‘difficulty in getting loans’ (35.83%) and ‘unavailability of subsidy on inputs’ (34.58%).

With regard to major technological/on farm constraints faced by the farm women were ‘non access to gender friendly technologies’(74.58%), ‘lack of technical knowledge about improved farming activities’ (73.75%), ‘unavailability of inputs at right time and right quantities’ (70.00%), ‘unavailability of farm machinery at right time’ (69.58%), ‘lack of Information and Communication Technologies’ (ICT’s) (68.33%), ‘lack of awareness about gender friendly technologies’ (66.25%), ‘lack of training programmes’(60.00%), ‘poor or non-access to information sources’ (60.00%), ‘lack of irrigation’ (56.25%), ‘scarcity of labour’ (55.42%), and ‘small size of land holding’ (50.83%). ‘Inadequate extension services (48.75%), ‘lack of direct extension contact’ (39.17%), ‘diminishing support from government for farm women’ (35.83%) and ‘qualitative degradation of inputs’ (22.08%) were other technological/on farm constraints faced by the farm women.

Similar findings were reported by Tiwari (2010), Warkade (2010), Girade and Shambharkar (2012), Chayal et al. (2013), Thakur (2013), Rani (2014), Pooja et al. (2016), Chauhan (2018) and Shankarrao (2018).

‘Being woman, it is difficult to perform certain farm operations’ with first rank was perceived by 89.17 per cent of farm women as a major socio-personal constraint. Farm women with less physical strength compared to men farmers often depended on men or agricultural labourers for more physically demanding tasks in farming. They also perceived that their lack of enough strength in

handling different agricultural tools and implements was restricting their efficiency in farming. ‘Lack of control over use of income’ (rank II) was deemed to be major constraint by most of the farm women (81.67%). Women in many households were not entitled to use and spend their self-earned income as well as family revenue for various family requirements due to the existing patriarchal society. Because of their lower educational background, men did not perceive women as capable of handling family financial concerns. As a result, many women felt deprived of their financial liberty at home and at work.

‘Male dominated society’ was witnessed by 71.67 per cent of farm women and it was ranked third in the socio-personal constraints. Since generations, a patriarchal structure had prevailed in society and women were considered as second to males in their homes, denied equal access to education as their male siblings, lacked asset ownership, financial autonomy and faced restrictions that hampered their social mobility. ‘Lack of ownership of assets (land and farm machinery/tools)’ (rank IV) was perceived as a constraint by 67.50 per cent of farm women. Many women do not have the ownership of land or machinery even though they are equal contributors on their farm. Women were not granted property alongside the male siblings in a household because as when they marry eventually, they become members of another household. In marital households, males hold the legal ownership of assets as the heads of the family due to existing patriarchal society. In some instances, women were given ownership of assets but in reality, that was not much beneficial to them and they did not have the autonomy of sale or further development of those assets.

‘Illiteracy’ with fifth rank was perceived as a constraint by 64.58 per cent of farm women. Farm women had less access to education because farming dependent households live in rural areas with few or no educational facilities or due to poor economic condition or due to the belief held by their parents that women do not need education. In certain circumstances, women have been denied access to higher education because their parents were unwilling to send their daughters away from home for study due to a traditional mindset. Illiteracy harmed women by limiting their knowledge, hindering them from making rational decisions and making them feel inferior to males. It also prevented them from actively participating in financial transactions and having social mobility.

Table 1. Constraints faced by farm women

‘Dependency on others’ (rank VI) was perceived as a constraint by 63.33 per cent of farm women. Farm women were subjected to subordination at home as males were head of the households. Furthermore, women with lower levels of education had to rely on others for financial transactions. Women depended on men for tasks which exert more physical strength. Traditional mindset prevailing in society restricts social participation of women which further forces them to be dependent on others. ‘Secondary status in decision making’ (rank VII) was experienced by 57.92 per cent of farm women. Women’s thoughts and decisions were often dismissed by other family members. Despite the fact that women manage all household affairs, their decisions were simply considered for a second opinion only with a preconception that they were not deemed to be of high quality or appropriate for the situation due to various reasons like their lack of education and awareness of external events.

‘Health problems’ (rank VIII) was experienced by 45.83 per cent of farm women. Farm women reside in rural areas where adequate health care facilities might not be easily accessible. Women generally have several responsibilities at home and on the farm, leaving them with little time to care for their health. Women sometimes suffer from health problems as a result of exhausting work at home and strenuous physical strain by work on the farm. ‘Lack of decision making power’ (rank IX) was experienced by 42.08 per cent of farm women. As a gesture of protection, women were frequently dominated by other family members and decisions were made on their behalf, particularly for young and elderly women. Women were denied autonomy in various financial and familial matters and they often lacked decision making power wherein final decision making authority was vested with the elders.

‘Lack of adequate time to work on farm due to domestic work’ (rank X) was experienced by 40 per cent of farm women. Along with working on the field, farm women must also manage domestic work, children raising and elderly care and household affairs. Many farm women have less support and assistance from other family members, resulting in insufficient time to carry out farm tasks. ‘Low self-confidence’ was ranked eleventh in socio- personal constraints and was experienced by 37.50 per cent of farm women. Farm women viewed themselves to have less awareness and knowledge and had low self- confidence due to lack of proper education and higher social participation.

‘Family and social conflict’ was ranked twelfth in socio-personal constraints and was experienced by 35 per cent of farm women. Some of the farm women experienced familial conflicts due to varied reasons like male dominance and disagreements between family members about various farm and financial affairs. They also encountered difficulty in a few occasions as a result of their social position. ‘Discouraging agricultural price policy’ (rank I) was perceived to be major economic constraint by 72.92 per cent of farm women. The majority of farm women thought agricultural pricing was unremunerative and unsatisfactory because most of them had marginal or small land holdings and the crop harvested from these holdings was limited and the income earned on the farm was insufficient to meet all of the farm women family needs.

‘Poor economic condition’ (rank II) was perceived to be major economic constraint by 63.75 per cent of farm women. Majority of farm women had marginal and small land holdings and a moderate level of income from varied sources. Farm women believed that they lacked the financial resources to expand their farming operations and invest in other sources of revenue and their poor financial situation prevented their children from pursuing higher education. ‘Discrimination in payment of wages’ (rank II) was perceived to be one of the major economic constraints by 63.75 per cent of farm women. In farm operations, men and women were paid differently for the same type of work for same duration of time because women were prejudiced to be less productive. As a result, farm women frequently experienced disparity in payment of wages as men were paid more than women.

‘Lack of credit’ (rank III) was perceived to be major economic constraint by 57.08 per cent of farm women. Most farm women sought financial credit for domestic and agricultural purposes due to their poor socioeconomic status. They frequently struggled to obtain loans for farm activities due to a shortage of sources of finance lending institutions at lower interest rates. ‘Costly agricultural inputs’ (rank IV) was perceived to be major economic constraint by 49.58 per cent of farm women. As most farm women had poor economic background, their purchasing powers was limited and were not able to afford agricultural inputs such as seed, fertilizers and pesticides which they thought to be expensive. ‘Difficulty in getting loans’ (rank V) was experienced by 35.83 per cent of farm women. Due to lengthy procedural formalities, small and marginal land holdings and illiteracy, farm women experienced difficulty in getting loans. ‘Unavailability of subsidy on inputs’ (rank VI) was experienced by 34.58 per cent of farm women. Farm women were not able to afford farm inputs owing to their poor economic level. As subsidy was unavailable for all farm inputs, they were forced to forego some critical inputs.

‘Non access to gender friendly technologies’ (rank I) was perceived to be major technological/on farm constraint by 74.58 per cent of farm women. Due to the fact that the majority of farm women live in rural regions and have limited access to extension services compared to male farmers, gender-friendly tools and technologies were not accessible to them. As the majority of agricultural operations needed a lot of physical strength which was difficult for farm women, the lack of gender-friendly technologies in their immediate vicinity was a big constraint to their farm performance. ‘Lack of technical knowledge about improved farming activities’ (rank II) was perceived to be major technological/on farm constraint by 73.75 per cent of farm women. Farm women had moderate extension contact and had less knowledge about improved farming practices due to less exposure to capacity building programmes. ‘Unavailability of inputs at right time and right quantities’ (rank III) was perceived to be major technological/on farm constraint by 70 per cent of farm women. Due to increased demand, most farm women encountered lack of farm inputs for purchase before the start of the cropping season. They also experienced shortage of farm machinery for critical farm activities. ‘Unavailability of farm machinery at right time’ (rank IV) was perceived to be major technological/on farm constraint by 69.58 per cent of farm women. Farm machinery availability shortages during critical stages of crop had a significant impact on farm operations and farm women who did not own farm machinery had to pay more on engaging farm machines. ‘Lack of Information and Communication Technologies’ (rank V) was perceived to be major technological/on farm constraint by 68.33 per cent of farm women. As majority of agricultural families live in rural areas in addition to most farm women being uneducated, they were unable to use ICTs to learn about new technology.

‘Lack of awareness about gender friendly technologies’ (rank VI) was perceived to be major technological/on farm constraint by 66.25 per cent of farm women. As a result of illiteracy and insufficient extension

services, farm women had little or no awareness about various available gender friendly tools and technologies. ‘Lack of training programmes’ (rank VII) was perceived to be major technological/on farm constraint by 60 per cent of farm women. Farm women perceived a dearth of training programmes that were tailored to their specific needs and timely requirements as women and owners of small farms. ‘Poor or non-access to information sources’ (rank VII) was perceived to be major technological/on farm constraint by 60 per cent of farm women. Illiteracy of farm women coupled with a lack of active social participation and inadequate access to extension services resulted in a scarcity of information about new farm technologies which ultimately obstructed higher yields on farms.

‘Lack of irrigation’ (rank VIII) was perceived to be major technological/on farm constraint by 56.25 per cent of farm women. Poor irrigation sources resulted in poorer yields and decreased farm income, making it difficult for farm women to make ends meet. ‘Scarcity of labour’ (rank IX) was perceived to be major technological/on farm constraint by 55.42 per cent of farm women. Due to migration of agricultural labour from rural areas to urban areas for better sources of livelihood, labour shortage was experienced specifically in peak crop seasons which resulted in delays in conducting critical farm tasks on time. ‘Small size of land holding’ (rank X) was perceived to be major technological/on farm constraint by 50.83 per cent of farm women. The size of the land holding had a huge impact on how different technologies were used on the farm and income from smaller land holdings was limited which was a major constraint to many farm women.

‘Inadequate extension services’ (rank XI) was perceived to be major technological/on farm constraint by 48.75 per cent of farm women. Many farm women had less access to extension services, particularly during peak crop seasons and also because extension service providers focused more on male farmers than farm women. ‘Lack of direct extension contact’ (rank XII) was experienced by 39.17 per cent of farm women. Extension service providers mostly focus on farmers as a whole, with farm women sometimes being left out and neglected. Due to their lower social participation, they lacked direct extension contact in the majority of situations and had to rely on their male counterparts for agricultural information.

‘Diminishing support from government for farm women’ (rank XIII) was experienced by 35.83 per cent of farm women. Farm women believed that the government gave little or no financial assistance and farm women oriented capacity building initiatives as well as specific marketing facilities for their produce were not adequate. ‘Qualitative degradation of inputs’ (rank XIV) was experienced by 22.08 per cent of farm women. Few farm women experienced low quality farm inputs specifically seeds. With much difficulty credit needed for farm inputs was gathered and when inputs quality was degraded, farm women not only experienced monetary loss but also missed critical time for certain farm operations.

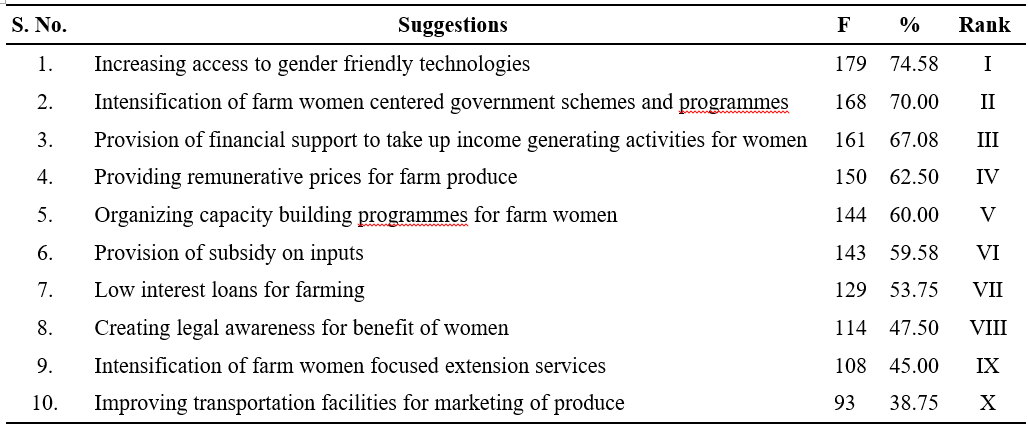

As major contributors on farm alongside men, farm women expressed suggestions to overcome the constraints faced by them. Suggestions were ranked in the descending order of the frequencies obtained and were depicted in table 2. Farm women suggested ‘increasing access to gender friendly technologies (74.58%, rank I), ‘intensification of farm women centered government schemes and programmes’ (70.00%, rank II), ‘provision of financial support to take up income generating activities for women (67.08%, rank III), providing remunerative prices for farm produce (62.50%, rank IV), organizing capacity building programmes for farm women (60.00%, rank V), provision of subsidy on inputs (59.58%, rank VI), low interest loans for farming (53.75%, rank VII), creating legal awareness for benefit of women (47.50%, rank VIII), intensification of farm women focused extension services (45.00%, rank XI) and improving transportation facilities for marketing of produce (38.75%, rank X) for overcoming their constraints.

Similar findings were reported by Bandode (2012), Machhliya (2014), Rani (2014) and Imam (2019).

Farm women might have experienced difficulty in performing farm operations due to heavy farm tools and implements. Women who might not have proficiency to use the farm machinery might have resorted to manual work for possible farm activities. Increased access to gender friendly tools and technologies might reduce the burden of heavy work on farm and would increase the farm women’s efficiency. Farm women might be expecting more farm women centered programmes which would aid them in providing finance, access to information and better marketing facilities. Farm women might be motivated in raising their standard of living by earning higher income through various avenues wherein they lacked initial financial investment and sincerely hoped for external financial support. Farm women who were majorly owners of marginal and small land holdings might have perceived that increased remunerative prices for produce would increase profits on their farms. Farm women were motivated towards building up of knowledge and skill to perform more efficiently in farm activities, thereby increasing their farm returns.

Table 2. Suggestions of farm women to overcome their constraints

Farm women wherein most of them were of poor economic background had perceived that availability of subsidy on inputs could reduce their financial burden. Low interest loans by various finance institutions could aid farm women to avoid distress sale and also they would be able to afford inputs for farm activities and family needs. Empowered farm women who had greater interest in legal aspects had perceived that woman should be provided legal awareness in order to fight the injustice and discrimination they faced in male dominated society. Increased extension services could increase access to capacity building programmes and information sources which would lead to more awareness, dissemination and adoption of improved technologies. Farm women wherein most of them reside in rural areas faced difficulty in marketing of produce due to lack of proper transportation facilities to better markets.

Many of the constraints experienced by farm women could be eliminated or their magnitude can be decreased by adequate interventions at family and societal level. Encouraging access to education for women will provide a farm woman with more decision making power and boosts their self-confidence. It also empowers farm women to be self-reliant and have control over their earnings. In addition to boosting farm women’s access to extension services, extension workers should focus on wider diffusion of gender-friendly technologies and increasing access to gender-friendly technologies to improve farm women’s productivity. Emphasis on increasing the favourable attitude of farm women towards improved agricultural technologies would render higher income even on smaller sized farms, improving the living conditions of farm women’s families. Farm women should be given more prominence in government support for farmers in order to keep the empowered women working in agriculture.

LITERATURE CITED

Bandode, S. 2012. A study on awareness and adoption of post-harvest management practices in maize among the farm women in Khargone district, M.P. M.Sc. (Ag.) Thesis. Rajmata Vijayaraje Scindia Krishi Vishwa Vidyalaya, Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India.

Chauhan, K.K. 2018. Participation of farm women in agricultural activities in Tikamgarh district (M.P.). M.Sc. (Ag.) Thesis. Jawaharlal Nehru Krishi Vishwa Vidyalaya, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India.

Chayal, K. Dhaka, B.L., Poonia, M.K., Tyagi, S.V.S and Verma, S.R. 2013. Involvement of farm women in decision-making in agriculture. Studies on Home and Community Science. 7(1): 35-37.

Girade, S and Shambharkar, Y. 2012. Profile of farm women and constraints faced by them in participation of farm and allied activities. Indian Journal of Applied Research. 1(12): 69-71.

Imam, S.J. 2019. Participation of farm women in agricultural activities and allied occupation. Ph.D. Thesis. Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth, Rahuri, Maharashtra, India.

Machhliya, M. 2014. A study on role of farm women in decision making in relation to vegetable cultivation in Teonthar block of Rewa district (M.P.). M.Sc. (Ag.) Thesis. Jawaharlal Nehru Krishi Vishwa Vidyalaya, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India.

Pooja, K., Arunima, K and Meera, S. 2016. Analysis of constraints faced by farm women in agriculture-A study in Samastipur district of Bihar. International Journal of Science, Environment and Technology. 5(6): 4522-4526.

Rani, S.N. 2014. Managerial role of farm women in Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh. M.Sc. (Ag.) Thesis. Acharya N.G. Ranga Agricultural University, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India.

Shankarrao, W.D. 2018. Decision making behaviour of farm women about agriculture. M.Sc. (Ag.) Thesis. Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth, Rahuri, Maharashtra, India.

Thakur, P.S. 2013. A study on role of farm women in decision making process in vegetable cultivation in Panagar block of Jabalpur district (M.P.). M.Sc. (Ag.) Thesis. Jawaharlal Nehru Krishi Vishwa Vidyalaya, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India.

Tiwari, N. 2010. Economic and Technological constraints facing farm women. International Journal of Rural Studies. 17(1): 1-5.

Warkade, P. 2010. A study on role of tribal farm women in decision making towards agricultural operations in Bichhia block of Mandla district, M.P. M.Sc. (Ag.) Thesis. Jawaharlal Nehru Krishi Vishwa Vidyalaya, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India.

- Genetic Divergence Studies for Yield and Its Component Traits in Groundnut (Arachis Hypogaea L.)

- Correlation and Path Coefficient Analysis Among Early Clones Of Sugarcane (Saccharum Spp.)

- Character Association and Path Coefficient Analysis in Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.)

- Survey on the Incidence of Sesame Leafhopper and Phyllody in Major Growing Districts of Southern Zone of Andhra Pradesh, India

- Effect of Organic Manures, Chemical and Biofertilizers on Potassium Use Efficiency in Groundnut

- A Study on Growth Pattern of Red Chilli in India and Andhra Pradesh