Effect of Sowing Window on Nodulation, Yield and Post – Harvest Soil Nutrient Status Under Varied Crop Geometries in Short Duration Pigeonpea (Cajanus Cajan L.)

0 Views

S. SOWJANYA*, C. NAGAMANI, S. HEMALATHA, CH. BHARGAVA RAMI REDDY AND V. CHANDRIKA

Department of Agronomy, S.V. Agricultural College, ANGRAU, Tirupati-517 502.

ABSTRACT

A field experiment was conducted during kharif, 2024 at wetland farm, S.V. Agricultural College, Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh. The experiment was laid out in a split-plot design and replicated thrice. The treatments consisted of four sowing windows viz., I FN of July (M1), II FN of July (M2), I FN of August (M3) and II FN of August (M4) assigned to main plots, three crop geometries viz., 30 cm x 10 cm (S1), 45 cm x 10 cm (S2) and 60 cm x 10 cm (S3) allotted to sub plots. Among the sowing windows tried, higher seed yield (957 kg ha-1) and stalk yield (2894 kg ha-1) was recorded with I FN of July (M1) and pigeonpea sown during II FN of August (M4) registered higher post-harvest soil available nutrient status. Crop geometry of 45 cm x 10 cm resulted in higher seed yield (833 kg ha-1) whereas 30 cm x 10 cm recorded higher stalk yield (2794 kg ha-1) and 60 cm x 10 cm resulted in higher post-harvest soil available nutrient status (N, P2O5, K2O:146, 24.6, 197 kg ha-1), number of nodules plant-1 (5.3, 9.7) and dry weight of nodules plant-1 (5.3, 79.4 mg) at 25 and 50 DAS.

KEYWORDS: Pigeonpea, crop geometry, sowing windows, nodules.

INTRODUCTION

Pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan L.) also known as red gram or tur or arhar, is an important pulse crop that is ranked second in India in terms of acreage and production and is the fifth most popular legume crop worldwide. It is originated in the regions of Angola and the Nile River in South Africa. Pigeonpea provides 20 – 22 % protein, 1.2 % fat, 65 % carbohydrates and 3.8

% ash. In India pigeonpea has high demand because it can supply high-quality protein in the diet, particularly to the vegetarian population. In India, the area under cultivation of redgram is 40.68 lakh ha with an annual production of 33.12 lakh tonnes. In Andhra Pradesh, it is cultivated in an area of 2.24 lakh ha with an annual production of 0.78 lakh tonnes (www.indiastat.com, 2022-23). The time of sowing acts as a biological clock, dictating the crop’s exposure to weather patterns, pests and nutrient dynamics. Meanwhile, plant spacing sets the stage for intra-specific interactions, influencing canopy architecture, root distribution and ultimately the yield. A strategic balance between these two factors can significantly enhance growth efficiency, water use and photosynthetic performance of short-duration pigeonpea. Exploring the synergy between sowing window and spatial arrangement is not just an agronomic necessity but, it is a key to unlock resilient and high-yielding pigeonpea production systems.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The field experiment was conducted at wetland farm, S.V. Agricultural College, Tirupati campus of Acharya N.G. Ranga Agricultural University, Andhra Pradesh. The soil of experimental field was sandy loam in texture, neutral in soil reaction, low in organic carbon (0.35%) and available nitrogen (240 kg ha-1), medium in available phosphorus (38.5 kg ha-1) and available potassium (235 kg ha-1). The experiment was laid out in a split-plot design and replicated thrice. The treatments consisted of four sowing windows viz., I FN of July (M1), II FN of July (M2), I FN of August (M3) and II FN of August (M4) assigned to main plots, three crop geometries viz., 30 cm x 10 cm (S1), 45 cm x 10 cm (S2) and 60 cm x 10 cm (S3) allotted to sub plots. A total rainfall of 1040.8 mm was received in 50 rainy days during the crop growing period. The nutrients were applied as per the recommended dose for the crop i.e., 20 – 50 – 0 kg N, P2O5 and K2O ha-1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

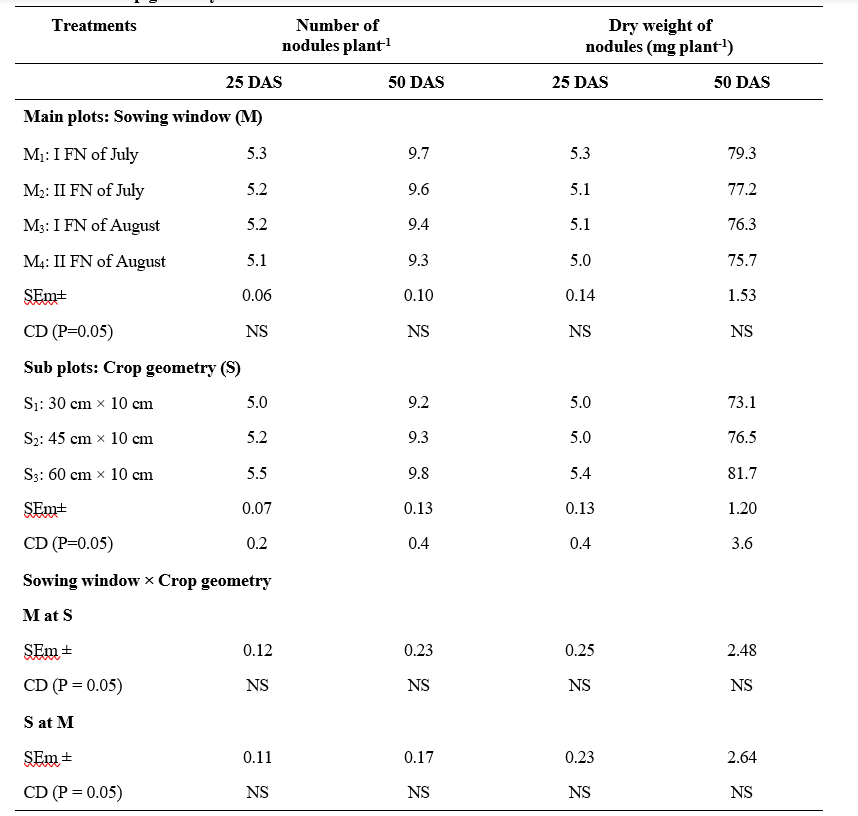

Number of nodules plant-1 and dry weight of nodules plant-1 at 25 and 50 DAS were not significantly influenced by the sowing window but were significantly influenced by crop geometries. The Interaction effect of sowing window and crop geometry was found to be non- significant.

Number of nodules plant-1 (5.3, 9.7) and dry weight of nodules plant-1 (5.3, 79.4 mg) at 25 and 50 DAS were significantly higher with the crop geometry of 60 cm x 10 cm (S3) compared to that of 45 cm x 10 cm (S2) except for the dry weight of nodules plant-1 at 25 DAS. Higher number of nodules plant-1 and dry weight of nodules plant-1 in pigeonpea at 25 and 50 DAS with crop geometry of 60 cm x 10 cm (S3) was due to more access of the plant to resources at wider spacing and also due to the reduction in inter row competition between plants. These findings are in support of Kaur and Saini (2018). The lower number of nodules plant-1 and dry weight of nodules plant-1 were recorded with crop geometry of 30 cm x 10 cm (S1) which were however comparable with that of 45 cm x 10 cm (S2).

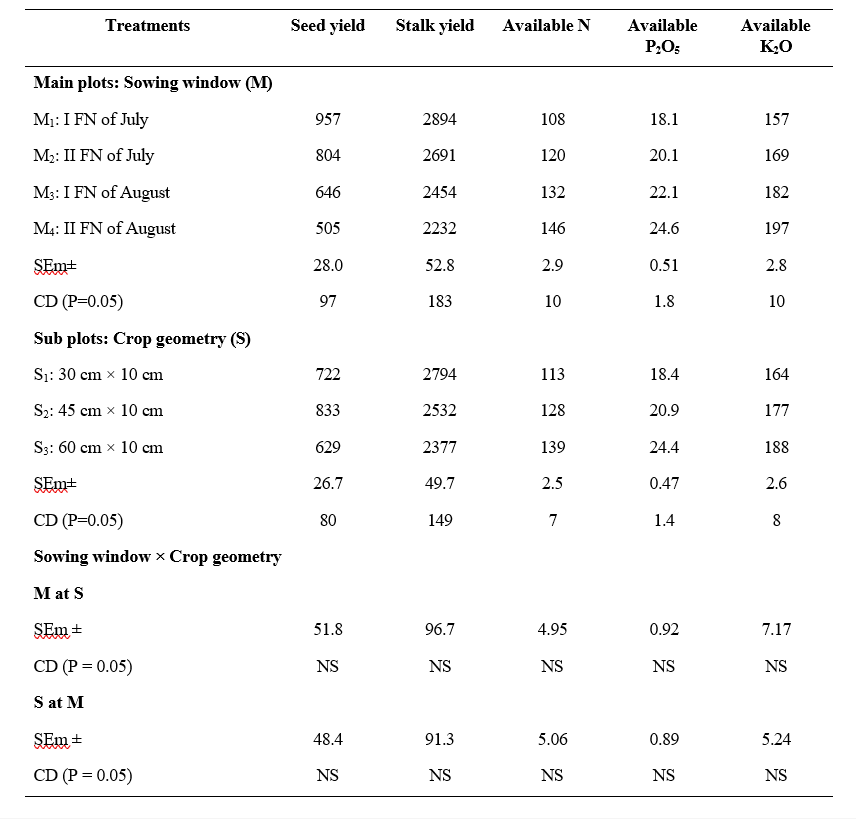

Significantly higher seed yield (957 kg ha-1) and stalk yield (2894 kg ha-1) was recorded when pigeonpea was sown during Ⅰ FN of July (M1) followed by sowing on ⅠI FN of July (M2), Ⅰ FN of August (M3) and II FN of August (M4) in the order of descent with significant disparity between each other. Higher seed yield realized with the pigeonpea sown during Ⅰ FN of July (S1) was due to the fact that the crop have experienced favourable weather conditions (light, temperature, rainfall) which might have facilitated the crop to maintain better source sink relationship. In addition to this there was enhanced yield attributing characters resulting in higher seed yield. These findings are in support of Dahariya et al. (2018), Patel et al. (2019), Kumar et al. (2018), Sandeep (2021) and Aruna and Kumar (2023). Higher stalk yield was recorded with early sown crop i.e., Ⅰ FN of July (M1) compared to delayed sowings, which was likely due to higher plant height, leaf area, number of branches plant-1 and greatly accumulation of dry matter. Similar findings on higher stalk yield were also reported by Dahariya et al. (2018) and Sandeep (2021). Sowing window and crop geometry exerted significant influence on seed and stalk yield of pigeonpea, while their interaction could not exert significant variation.

Among the crop geometries tested, 45 cm x 10 cm (S2) resulted in significantly higher seed yield (833 kg ha-1). The next best crop geometry was 30 cm x 10 cm (S1) which was significantly superior to that of 60 cm x 10 cm (S3). Higher seed yield with the crop geometry of 45 cm x 10 cm (S2) might be due to optimum plant stand that have enabled the plant for better resource utilisation throughout the growing period. Significantly lower seed yield recorded with the crop geometry of 60 cm x 10 cm (S3) was due to lower plant population unit area-1, though the individual plants at this crop geometry had higher yield attributing characters. Similar findings were observed with Ammaiyappan et al. (2021) Sujathamma et al. (2022) and Abhishek et al. (2023).

Significantly higher stalk yield (2794 kg ha-1) was recorded with 30 cm × 10 cm (S1) followed by that with 45 cm × 10 cm (S2). Significantly lower stalk yield (2377 kg ha-1 ) was recorded with 60 cm × 10 cm (S3). Higher stalk yield with the crop geometry of 30 cm × 10 cm (S1) was due to higher number of plants per unit area-1, coupled with superiority of growth characters like plant height, leaf area index and dry matter accumulation. The above findings were in accordance with that of Kavin et al. (2018), Tungoe et al. (2018), Shinde et al. (2021), Tuppad et al. (2012), Bansal et al. (2023) and Saikumar (2024).

Post harvest soil nutrient status was significantly influenced by sowing windows and crop geometries, but the interaction between them was noticed to be non-significant. With reference to the varied sowing windows tried, pigeonpea sown during II FN of August (M4) recorded significantly higher post-harvest soil available nitrogen (146 kg ha-1), phosphorus (24.6 kg ha-1) and potassium (197 kg ha-1) compared to that of Ⅰ FN of August (M3). The later was significantly superior than that of ⅠI FN of July (M2). Significantly lower post- harvest soil available nutrient status was noticed with the crop sown during Ⅰ FN of July (M1). This might be due to higher nutrient uptake by the crop sown during Ⅰ FN of July (M1) to accumulate maximum dry matter resulting in greater reduction in soil available nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium at harvest. These results corroborate with the findings of Dash et al. (2024).

Pigeonpea sown at a crop geometry of 60 cm x 10 cm (S3) resulted in significantly higher post-harvest soil available nitrogen (139 kg ha-1), phosphorus (24.4 kg ha-1) and potassium (188 kg ha-1). This might be due to lower plant population unit area-1 which reduced the uptake of nutrients and increased the post-harvest soil available nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium. The next crop geometry recorded higher post-harvest soil available nutrients was 45 cm x 10 cm (S2) which was significantly superior to that of 30 cm x 10 cm (S1). These results are

Table 1. Number of nodules plant-1 and dry weight of nodules (mg plant-1) of pigeonpea as influenced by sowing window and crop geometry

Table 2. Seed, stalk yield (kg ha-1) and post-harvest soil available N, P2O5 and K2O (kg ha-1) of pigeonpea as influenced by sowing window and crop geometry

in confirmity with that of Prathibha (2017), Dathamma (2023) and Saikumar (2024).

With regard to the sowing windows tried, pigeonpea sown during I FN of July (M1) recorded higher seed and stalk yields, indicating that early sowing is the most favourable sowing window for maximizing productivity. Among the plant geometries tested, 45 cm x 10 cm resulted in higher seed yield whereas stalk yield was recorded higher with crop geometry of 30 cm x 10 cm. Crop sown during II FN of August (M4) with crop geometry of 60 cm x 10 cm registered higher post-harvest soil available nutrient status due to lower plant population unit area-1 which reduced the uptake of nutrients and increased the post-harvest soil available nutrient status. Number of nodules plant-1 and dry weight of nodules plant-1 at 25 and 50 DAS was not significantly influenced by the sowing windows. Crop geometry of 60 cm x 10 cm resulted in highest number of nodules plant-1 and dry weight of nodules plant-1 at 25 and 50 DAS. Overall, sowing of short duration pigeonpea during kharif, with proper sowing window and optimum crop geometry results in maximum productivity.

LITERATURE CITED

Abhishek, K., Kumar, A.N., Naseeruddin, R and Sandhyarani, P. 2023. Influence of high-density planting on yield parameters of super early and mid-early varieties of redgram (Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp.). Andhra Pradesh Journal of Agricultural Sciences. 9(4): 267-270.

Ammaiyappan A., Paul, R.A.I., Veeramani, A and Kannan, P. 2021. Effect of agronomic manipulations on morpho-physiological and biochemical responses of rainfed redgram [Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp.). Legume Research. DOI: 10.18805/LR-4650.

Aruna, E and Kumar, K.S. 2023. Influence of sowing time on varied duration redgram genotypes in YSR kadapa district. International Journal of Plant & Soil Science. 35(18): 1983-1988.

Bansal, K.K., Kumar, V., Attri, M., Jamwal, S., Kumari, A and Kour, K. 2023. Impact of spacing variability on pigeon pea genotypes: A study of growth evaluation, productivity, quality, and profitability. In Biological Forum–An International Journal. 15(7): 157-163.

Dahariya, L., Chandrakar, D.K and Chandrakar, M. 2018. Effect of dates of planting on the growth characters and seed yield of transplanted pigeonpea [Cajanus cajan (L.) Mill Sp.]. International Journal of Chemical Studies. 6(1): 2154-2157.

Dash, S., Murali, K., Bai, S.K., Rehman, H.A and Sathish, A. 2024. Influence of sowing window and planting geometry on pigeonpea nutrient uptake, quality and yield. Mysore Journal of Agricultural Sciences. 58(1): 387-396.

Dathamma, B.V. 2023. Optimization of sowing window and spacing for enhanced seed production in dhaincha (Sesbaniu aculeata L.). M.Sc. (Ag.) Thesis. Acharya N.G. Ranga Agricultural University, Guntur, Andhra Pradesh, India.

Kaur, K and Saini, K.S. 2018. Performance of pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan L.) under different row spacings and genotypes. Crop Research. 53 (3-4): 135-137.

Kavin, S., Subrahmaniyan, K and Mannan, S.K. 2018. Optimization of plant geometry and NPK levels for seed and fibre yield maximization in sunhemp [Crotalaria juncea L.] genotypes. Madras Agricultural Journal. 105(4-6): 156-160.

Kumar, A., Dhanoji, M.M and Meena, M.K. 2018. Phenology and productive performance of pigeonpea as influenced by date of sowing. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry. 7(5): 266- 268.

Patel, H.P., Gurjar, R., Patel, K.V and Patel, N.K. 2019. Impact of sowing periods on incidence of insect pest complex in pigeonpea. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies. 7(2): 1363-1370.

Prathibha, S.K. 2017. Effect of sowing dates, spacing and topping on sunhemp (Crotalaria juncea L.) seed production. M.Sc. (Ag.) Thesis. Mahatma Phule Krishi Vidyapeeth, Rahuri, Maharastra.

Saikumar, M. 2024. Performance of ultra short duration redgram varieties under different plant geometries. M.Sc. (Ag.) Thesis. Acharya N.G. Ranga Agricultural University, Guntur, Andhra Pradesh, India.

Sandeep, G. 2021. Cultivar and sowing date effect on productivity of redgram (Cajanus cajan L.). Doctoral dissertation. Acharya NG Ranga Agricultural University, Guntur, Andhra Pradesh, India.

- Effect of Sowing Window on Nodulation, Yield and Post – Harvest Soil Nutrient Status Under Varied Crop Geometries in Short Duration Pigeonpea (Cajanus Cajan L.)

- Nanotechnology and Its Role in Seed Technology

- Challenges Faced by Agri Startups in Andhra Pradesh

- Constraints of Chcs as Perceived by Farmers in Kurnool District of Andhra Pradesh

- Growth, Yield Attributes and Yield of Fingermillet (Eleusine Coracana L. Gaertn.) as Influenced by Different Levels of Fertilizers and Liquid Biofertilizers

- Consumers’ Buying Behaviour Towards Organic Foods in Retail Outlets of Ananthapuramu City, Andhra Pradesh