A Profile Study of Farmers Affected by Human Wildlife Conflict in Kurnool District of Andhra Pradesh

0 Views

K. RAVEENA*, S. RAMALAKSHMI DEVI, P. GANESH KUMAR, C. PRATHYUSHA AND T. LAKSHMI

Department of Agricultural Extension Education, S.V. Agricultural College, ANGRAU, Tirupati-517 502.

ABSTRACT

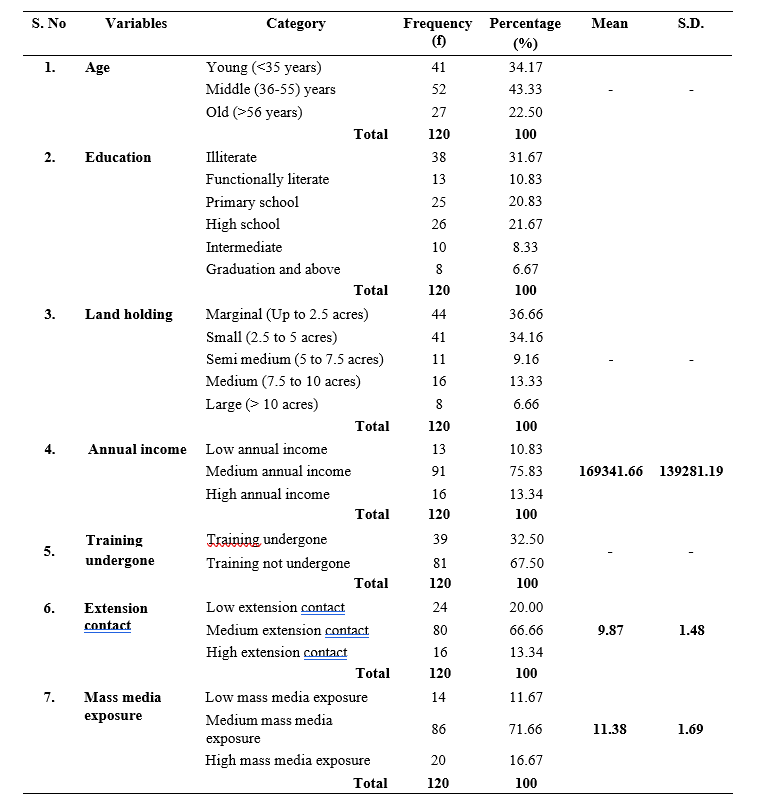

The present study was carried out to know the profile of farmers affected by human-wildlife conflict in Kurnool district of Andhra Pradesh over a randomly drawn sample of 120 respondents. The results revealed that the majority of the farmers were in middle age (43.33%), illiterate (31.67%) and had marginal level of land holding (36.66%). Most of them had a medium level of annual income (75.83%), had not undergone any formal training (67.50%) and had medium levels of extension contact (66.66%), mass media exposure (71.66%). These socio-economic characteristics revealed that, sample population with moderate access to resources and limited exposure to advanced agricultural practices or mitigation strategies. The study emphasizes the importance of tailored awareness programs, extension services and policy interventions that consider the specific demographic and socio-economic background of these farmers to reduce vulnerability to human wildlife conflict and improve their adaptive capacity.

KEYWORDS: Human-wildlife conflict, Profile.

INTRODUCTION

The total forest cover in Andhra Pradesh is 37,258 square kilometres, which accounts for 23.00 per cent of the geographical area (FSI, 2023). In Kurnool district, forest cover was reported as 1,780 square kilometres, forming about 10.34 per cent of the district total area (Global Forest Watch, 2023). While these forested regions play a critical role in sustaining biodiversity and maintaining ecological balance, they have also become hotspots for Human-Wildlife Conflict (HWC). Species involved in HWC are leopards, wild boars and deer increasingly venture into human settlements in search of food and water. This often resulted in crop damage, livestock predation, property destruction and injuries to humans. The frequent interactions between humans and wildlife highlight the urgent need for sustainable forest management, community awareness programs and effective conflict mitigation strategies to ensure both wildlife conservation goals and human safety issues.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The present study was conducted by following exploratory research design. Kurnool district of Andhra Pradesh was purposively selected based on its high incidence of human-wildlife conflict. From the selected district, two mandals were selected through simple random sampling method. From each of the selected mandal, three villages were selected through simple random sampling procedure thus making a total of six villages, 20 respondents were selected from each village using simple random sampling procedure thus making a total of 120 respondents. After a thorough review of literature and consultations with experts a set of nine variables were selected. The data was collected through a structured interview schedule and analysed using mean and standard deviation for drawing meaningful interpretations.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The respondents were distributed based on their selected profile characteristics and the results were presented in the Table 1.

Age

From the Table 1, it was clear that majority (43.33%) of the respondents belonged to middle age category followed by young age (34.17%) and old age (22.50%) categories respectively. The reason behind this was middle aged respondents were actively engaged in farming and related livelihoods, making them more likely to have direct and frequent encounters with wildlife, which made their perceptions crucial for understanding conflict dynamics and assessing the effectiveness of mitigation measures. This finding was in conformity with the findings of Islam (2015) and Mukesh (2017).

Education

From the Table 1, it was evident that majority (31.67%) of the respondents were illiterate followed by high school (21.67%), primary school (20.83%), functionally literate (10.83%), intermediate (8.33%) and graduation and above (6.67%) level of education respectively. The key reasons for the trend was low awareness on education and schools were either unavailable or located far from villages, making access difficult. Additionally, economic hardship had forced many families to prioritize farm labour and household responsibilities over formal education, leading to early dropouts or complete avoidance of schooling. This finding was in conformity with the finding of Naveen (2023).

Land holding

It was implied from the Table 1, that a majority (36.66%) of the respondents were marginal followed by small (34.16%), medium (13.33%), semi-medium (9.16%) and large (6.66%) farmers respectively. This distribution may be attributed to overall landholding pattern in the region, where fragmented and small- sized holdings were more prevalent due to population pressure and generational division of land. In areas prone to human-wildlife conflict, marginal farmers were significant in number, as they tend to cultivate on the fringes of forests or reserve areas, which were more vulnerable to wildlife intrusion. This finding was in conformity with the finding of Singh (2023) and Deepak (2022).

Annual Income

It was noticed from Table 1, that majority (75.83%) of the respondents belonged to medium annual income level followed by those with high (13.34%) and low (10.83%) levels of annual income respectively. The majority of the respondents belonged to medium income, this may allowed them to use basic mitigation measures like scare devices or community monitoring, although they likely remained limited in accessing advanced or costly interventions such as electric fencing or insurance coverage which was occurred due to human wildlife conflict. This finding was in conformity with the finding of Jadhav (2020).

Training Undergone

It was evident from Table 1, that majority (67.50%) of the respondents were not undergone training and 32.50 per cent of the respondents have undergone training respectively. The majority of the respondents were not undergone training due to the reason that many farmers resided in remote and forest adjacent areas where poor infrastructure and logistical challenges had limited their access to formal training programs. Additionally, there appeared to had with low levels of awareness regarding the availability and importance of such training, largely due to inadequate outreach by government departments and agricultural extension services. This finding was in conformity with the finding of Venkatesan and Vijayalakshmi (2015).

Extension Contact

A desultory look at the Table 1 disclosed that more than half (66.66%) of the respondents have medium extension contact followed by 13.34 per cent of them with high extension contact and only 20.00 per cent of them with low extension contact respectively. This was because majority of the respondents have frequent interaction with extension agents which helped them to get aware of latest crop varieties, technologies, new mitigation measures and compensation schemes. This finding was in conformity with the finding of Mukesh (2017) and Singh (2023).

Mass media exposure

It was noticed from Table 1, that majority (71.66%) of the respondents had medium mass media exposure, followed by those with high (16.67%) and low (11.67%) of mass media exposure respectively. The findings indicated that, medium portion of farmers have access to information through media such as radio, television and mobile phone, their usage was often irregular or limited to general content. This finding was in conformity with the findings of Mukesh (2017) and Neha (2022).

The study concludes that a large proportion of the respondents affected by human-wildlife conflict in Kurnool district fall into the categories of middle-aged, illiterate, and marginal landholders. These characteristics suggest a group that may be more vulnerable to wildlife intrusions due to limited resources, education, and institutional support. Despite moderate levels of income and exposure to extension and mass media services,

Table 1. Distribution of farmers according to their profile (n=120)

the lack of formal training and educational attainment hinders the effective adoption of advanced conflict mitigation techniques. These findings underscore the urgent need for capacity-building initiatives such as location-specific training programs, community-based conflict management strategies, and better accessibility to extension and information services. Moreover, improved infrastructure and policy-level interventions should be designed to target the most affected segments of the farming population. Strengthening institutional support and ensuring participatory approaches in planning and implementation can enhance the resilience of these communities against recurring human-wildlife conflict.

LITERATURE CITED

Deepak, C. M. 2022. Human wildlife conflict in the vicinity of Ranthambore tiger reserve: farmers perspective. Ph.D. Thesis. ICAR-National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal. Haryana.

Forest Survey of India (FSI). 2023. India State of Forest Report 2023. Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India.

Global Forest Watch. 2023. Kurnool district, Andhra Pradesh – Forest cover and loss data. Retrieved from https: //www.globalforestwatch.org

Islam, M. A., Rai, R., Quli, S. M. S. and Tramboo, M. S. 2015. Socio-economic and demographic descriptions of tribal people subsisting in forest resources of Jharkhand, India. Asian Journal of Bio Science. 10(1): 75-82.

Jadhav, H.S. 2020. Perception of farmers about zero budget natural farming. M.Sc. (Ag.) Thesis. Vasantrao Naik Marsthwada Krishi Vidyapeeth, Parbani, Maharastra, India.

Mukesh, K. 2017. Assessment of livestock owners- wildlife conflict in the vicinity of National Park. Ph.D. Thesis. ICAR-National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal, Haryana.

Naveen, K. N. 2023. Economic assessment of human- wildlife conflicts in agriculture. Ph.D. Thesis. ICAR-Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi.

Neha, M. B. 2022. Measurement of knowledge, attitude and practices among the public residing around the Indian Flying Fox (Pteropus Medius) roosting site. M.Sc. (Ag.) Thesis. Kerala Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Wayanad, Kerala.

Singh, A. 2023. Reckoning farmers-wildlife and tolerance in the proximity of Panna Tiger Reserve. M.Sc. Thesis. Dr. Rajendra Prasad Central Agricultural University, Pusa, Bihar.

Venkatesan, P and Vijayalakshmi, P. 2015. Training needs of farm women towards entrepreneurial development. Journal of Extension Education. 27(1): 539-547.

- Effect of Sowing Window on Nodulation, Yield and Post – Harvest Soil Nutrient Status Under Varied Crop Geometries in Short Duration Pigeonpea (Cajanus Cajan L.)

- Nanotechnology and Its Role in Seed Technology

- Challenges Faced by Agri Startups in Andhra Pradesh

- Constraints of Chcs as Perceived by Farmers in Kurnool District of Andhra Pradesh

- Growth, Yield Attributes and Yield of Fingermillet (Eleusine Coracana L. Gaertn.) as Influenced by Different Levels of Fertilizers and Liquid Biofertilizers

- Consumers’ Buying Behaviour Towards Organic Foods in Retail Outlets of Ananthapuramu City, Andhra Pradesh