Nanotechnology and Its Role in Seed Technology

0 Views

TJ. Anitha Rose *, B. Rupesh Kumar Reddy, S. Vasundhara and G. Narasimha

Department of Seed Science and Technology, S.V. Agricultural College, ANGRAU, Tirupati-517 502.

ABSTRACT

Nanotechnology, an emerging field of material science, deals with materials smaller than 100 nanometres and has wide applications in plant and animal research. In agriculture, particularly in seed science, nanoparticles are used to enhance germination, seed vigour and tolerance to environmental stresses. Their effects, however, can be beneficial or harmful, depending on factors such as composition, size, shape, surface modification, concentration, plant species and environment. Studies highlight that nanoparticle size and concentration are crucial in determining their biological impact. This review discusses the role of nanoparticles in seed technology and their potential benefits for sustainable agriculture.

KEYWORDS: Nano particles, Seed technology, Seed germination, Seed vigour.

INTRODUCTION

Nanotechnology refers to the branch of science and engineering devoted to designing, producing and using structures, devices and systems by manipulating atoms and molecules at nanoscale. “Nano” means one-billionth (10-9), thus nanotechnology deals with materials measured in a billionth of a meter. Nanoparticles are atomic or molecular aggregates with at least one dimension between 1 and 100 nm (Roco, 2003). Nanoparticles have a small size and a high surface-to-volume ratio, which confer to them remarkable chemical and physical properties in comparison to their bulk counterparts (Roduner, 2006). Due to their unique properties nanoparticles are suitable for use in different fields, such as life science, electronics and chemical engineering (Jeevanandam et al., 2018).

National nanotechnology initiative is U.S government research and development initiative, has given the definition of nanotechnology as “Understanding and control of matter at dimensions between approx. 1 and 100 nanometers. Nanoparticles are widely used in different aspects of daily life activities and have a significant effect on society, economy and the environment (Nel et al., 2006). Nanotechnology has generated various types of nanoparticles (NPs) with differences in size, shape, surface charge and surface chemistry (Albanese et al., 2012).

Nanotechnology has recently attracted significant interest in plant science due to its potential to develop compact, efficient systems for enhancing seed germination, growth and protection against biotic and

abiotic stresses. Seeds, often described as nature’s nano- gift, can have their full potential harnessed through nanotechnology. Various seed quality enhancement techniques exist, each offering distinct benefits, but nanoparticle treatments are particularly promising. Such treatments can accelerate germination, increase seedling strength, vigour and improve overall seed quality. Metal-based nanoparticles are widely applied in these contexts (Zhu and Nguguna, 2014). Consequently, many researchers are exploring the use of metal oxide nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes to penetrate the seed coat and promote germination.

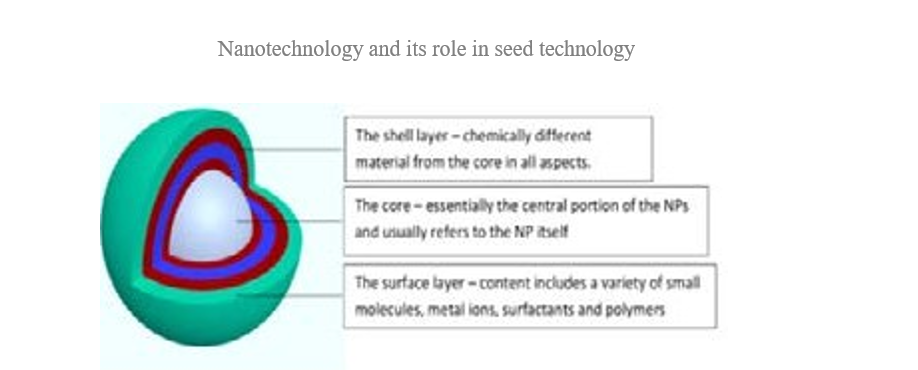

Composition of nanoparticle

Nanoparticles consist of three layers: the surface layer, the shell layer, and the core. The surface layer usually consists of a variety of molecules such as metal ion, surfactants and polymers. Nanoparticles may contain a single material or consist of a combination of several materials. Nanoparticles can exist as suspensions, colloids, or dispersed aerosols depending on their chemical and electromagnetic properties.

CLASSIFICATION OF NANOPARTICLES (NPs)

Nanoparticles are broadly divided into various categories depending on their morphology, size and chemical properties. Based on physical and chemical characteristics, some of the well-known classes of nanoparticles are given as below.

1. CARBON-BASED NANOPARTICLES

Fullerenes and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) represent two major classes of carbon-based NPs. Fullerenes contain nanomaterial that are made of allotropic forms of carbon. Carbon nano tubes (CNTs) are elongated, tubular structure, 1–2 nm in diameter (Ibrahim, 2013).

1. METAL NANOPARTICLES

Metal nanoparticles are usually defined as particles of metal atoms with diameters between 1 nm and about a few hundreds of nanometres. Purely made of metal precursors. Types of metal nanoparticles:

- Metal organic Frameworks (MOF)

- Metal Nanoparticle

- Metal Sulfide Nanoparticle

- Metal oxide Nanoparticle

- Doped Metal/Metal Oxide Nanoparticle

2. CERAMICS NANOPARTICLES

These are inorganic, non-metallic solids that can exist in either amorphous or crystalline forms. They are widely used because of their favourable properties, including chemical inertness, high thermal stability and durability.

3. SEMICONDUCTOR NANOPARTICLES

Semiconductor materials have unique physical properties and possess properties between metals and non-metals. Semiconductor nanoparticles possess wide bandgaps and therefore showed significant alteration in their properties. These are the fluorescent materials.

4. POLYMERIC NANOPARTICLES

These nanomaterials (NMs) are primarily derived from organic matter, excluding carbon-based and

inorganic nanomaterials. By leveraging non-covalent (weak) interactions for self-assembly and molecular design, organic nanomaterials can be structured into desired forms such as dendrimers, micelles, liposomes and polymer nanoparticles.

Eg: Chitosan nanoparticles

5. LIPID-BASED NANOPARTICLES

Generally, a lipid nanoparticles is characteristically spherical with diameter ranging from 10 to 1000 nm. Like polymeric nanoparticles, lipid nanoparticles possess a solid core made of lipid and a matrix contains soluble lipophilic molecules. Characteristically spherical and contain lipid moieties. Effectively used in many biomedical applications.

APPROACHES FOR SYNTHESIS OF NANOPARTICLES

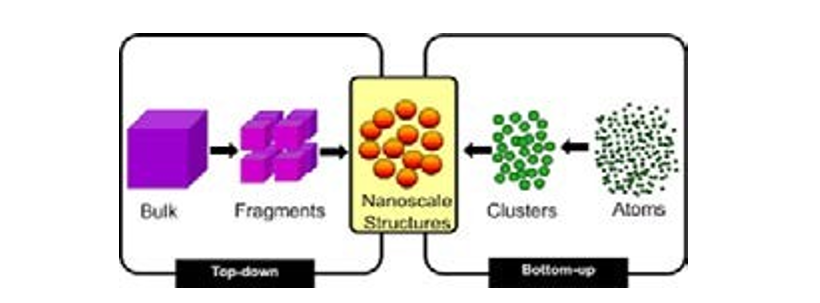

a) Top-down approach

This method involves breaking down materials into their basic building blocks. It often relies on chemical or thermal techniques such as milling, grinding, or cutting. The process is energy-intensive and generally more expensive compared to bottom-up approaches.

b) Bottom-up approach

This approach involves constructing complex systems by assembling simple, atomic-level components. It enables the production of nanostructures with fewer defects and a more uniform chemical composition, enhancing their performance and reliability.

SYNTHESIS OF NANOPARTICLES

1) Physical method

The synthesis of nanoparticles often requires

significant time and energy, typically involving high temperatures and pressures. Common techniques include laser ablation, ultrasonication, photoirradiation, radiolysis, solvated metal atom deposition and vaporization. These methods, while effective, can be resource-intensive and may limit large-scale or cost- effective production.

1) Chemical Synthesis Method

This is a straightforward method for synthesizing nanoparticles, based on a bottom-up approach. It requires relatively low energy, cost-effective and is suitable for both in vivo and in vitro applications, offering versatile uses. However, when performed at low temperatures, the use of toxic and stabilizing agents can pose environmental and health hazards, making the process potentially harmful.

2) Biological methods

Green synthesis techniques typically employ non- toxic chemicals, benign solvents, and biological extracts or systems. These approaches are considered safe, environmentally friendly and sustainable alternative to conventional physical and chemical methods for nanoparticle fabrication. They are particularly well- suited for in vivo applications, drug delivery and the development of bioactive agents. Additionally, green synthesis is easy to perform, efficient, eco-friendly and requires less energy, making it a preferred method for sustainable nanotechnology applications.

UPTAKE AND TRANSLOCATION OF NANOPARTICLES IN PLANTS THORUGH ROOTS AND LEAF SURFACE

The interaction between nanoparticles and plants is affected by factors such as particle size, shape, and surface characteristics. The way plants absorb nanoparticles depends largely on the method of exposure. In roots, nanoparticles are taken up primarily via two pathways: the apoplastic pathway, which involves movement through cell walls and intercellular spaces whereas symplastic pathway involves transport through the cytoplasm of connected cells via plasmodesmata. Many types of nanoparticles reach the endodermis, the symplastic pathway allowing the entry of nanoparticles through the plasma membrane, this pathway is more important than the apoplastic pathway (Qian et al., 2013). Different types of nanomaterials such as Au, Ag, Al2O3, CeO2, Cu, CdS, Fe2O3, Fe, SiO2, TiO2, Zn, ZnO, ZnSe reports their impact on plant physiology and the development of plants (Singla et al., 2019). The cell wall of the plant is a complex matrix, where only a few materials pass through the plant cell (Deng et al., 2014).

Most of the nanoparticles bind to the carrier protein via ion channels endocytosis, form new pores and enter plant cell. After entering they are transported from one cell to the other via plasmadesmata. Entry depends on the size of the nanoparticles. Small sized nanoparticles enters easily through the cell wall. Hydrophobicity and chemical inertness of the leaf cuticle prevents their entry. Newly grown leaves in plants and undeveloped cuticles in flowers may have a higher probability of nanoparticles entering the leaves and developing from its effects (Honour et al., 2009). There are two routes for the uptake of nanoparticle solution through the cuticle layers, non- polar solutes enter through lipophilic pathway and polar solutes through aqueous pores.

The stomatal pathway is a confirmed route for the uptake of foliar-applied nanoparticles (NPs), allowing them to move from leaf surfaces to other plant tissues (A. Avellan et al., 2021). Upon contact, nanoparticles adhere to the plant surface through electrostatic, hydrophobic, and van der waals interactions. Their uptake is influenced by particle polarity: both positively and negatively charged nanoparticles can be absorbed by leaves and translocated to roots, whereas root uptake occurs predominantly for negatively charged nanoparticles. The most direct evidence comes from Avellan et al. (2017), who exposed Arabidopsis to both positively and negatively charged gold nanoparticles (~12 nm) and found that “positively charged NPs induced a higher mucilage production and adsorbed to it, which prevented translocation into the root tissue,” while negatively charged NPs “did not adsorb to the mucilage and were able to translocate into the apoplast”.

IMPACT OF NANOTECHNOLOGY IN SEED TECHNOLOGY

Nanotechnology plays a significant role in advancing seed technology by enhancing germination and promoting vigorous seedling growth. The core claims about nano-priming enhancing germination and enzyme activation are well-supported. Mahakham et al. (2017) demonstrated that silver nanoparticles at 5-10 ppm significantly improved rice seed germination and enhanced α-amylase activity, directly confirming key mechanistic claims. Nano fertilizers enable precise and efficient delivery of essential nutrients, improving seedling nutrition and overall growth. Nano pesticides target specific pathogens and pests, reducing chemical use and environmental impact. Siddaiah et al. (2018) showed that the treatment of millet seeds with chitosan nano-particles resulted in alteration of the innate immune system of the plants and increased resistance against pathogens. Moreover, nanoparticles can serve as carriers for gene delivery, supporting crop improvement and stress tolerance. Collectively, these applications result in higher yields, enhanced resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses, and promote sustainable agricultural practices, positioning nanotechnology as a transformative tool in modern seed science.

NANOPARTICLES IN IMPROVING SEED GERMINATION, QUALITY AND YIELD

Nanoparticles can exert both stimulatory and inhibitory effects on seed germination. Their positive effects are primarily due to enhanced activities of α-amylase and protease enzymes, increased protein synthesis and improved water absorption within the seed all of which promote early and uniform germination. Conversely, nanoparticles can also trigger the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to oxidative stress that damages DNA, proteins and cell membranes (Moore, 2006). The presence of nanoparticles in the growth medium can alter water balance through the seed coat, thereby affecting germination. Multiple studies confirm that size, concentration, and nanoparticle type significantly affect germination outcomes across various plant species (K. Adhikari et al., 2021). Furthermore, nanoparticles can help break seed dormancy, act as nano- fertilizers or pesticides, and enhance enzymatic activity. As they degrade in soil, nanoparticles release ions that plants absorb as nutrients, contributing to growth and productivity.

POTENTIAL RISKS/ BIOSAFETY CONCERNS

1. CYTOTOXICITY OF NANOPARTICLES

Pesticides and fertilizers in nano formulations, when air borne – deposit on above ground plant parts

– plugging of the stomata which hinders the gaseous exchange and create toxic barrier on the stigma preventing the penetration of the pollen tube. It may also enter the vascular system and hinder the translocation process, preventing the fertilization and seed formation.

Kumari et al., 2012 documented cellular-level effects including chromosomal aberrations and micronucleus formation. M. Thiruvengadam et al., 2024 confirms nanoparticles induce cytotoxicity through ROS generation leading to cell death.

2. POTENTIAL RISKS OF NANOTECHNOLOGY

Chemical hazards on edible plants after treatment with high concentration. Nanomaterial generated free radicals in living tissue leading to DNA damage. The nanotoxicity studies in agriculture are very limited and it causes a potential risk to plant, animal microbes and even humans. There are some negative effects of Nanomaterials on biological systems and the environment caused by nanoparticles. Nano materials are able to cross biological membranes and access cells tissues and organs that larger sized particles normally cannot. Therefore, nanotechnology should be carefully evaluated before increasing the use of the nano agro materials.

CHALLENGES IN NANOTECHNOLOGY

Despite its potential, nanotechnology in seed science faces several challenges. The major concern is the toxicity of nanoparticles, which can negatively affect seed germination, plant growth, and soil microorganisms.

Lack of standardized methods for nanoparticle synthesis, application and dosage limits consistent results. Environmental accumulation and bioaccumulation pose ecological risks. Limited understanding of nanoparticle interactions within plant systems further complicates their safe use. Additionally, high production costs, regulatory issues, and insufficient safety guidelines hinder large- scale application. Addressing these challenges through detailed risk assessment and sustainable practices is crucial for the safe integration of nanotechnology in seed science. Producing nanomaterials in large volumes while maintaining consistent quality and affordable cost remains a major challenge. The gap between basic research and application is another challenge in nanotechnology like several technologies.

The interaction between nanoparticles and plant cells plays a crucial role in advancing plant nanotechnology. Engineered nanoparticles are increasingly applied to improve crop productivity by enhancing seed germination, vigour, and resistance to both biotic and abiotic stresses. These particles can accumulate in various plant parts such as roots, stems, and leaves, influencing physiological processes like growth, respiration, transpiration, and biomass formation. Beneficial effects are generally observed at lower nanoparticles concentrations, which differ among crops. Nonetheless, careful consideration of biosafety and environmental impacts is essential, as nanomaterials and nano waste may pose future risks to agricultural ecosystems.

LITERATURE CITED

Adhikari, K., Mahato, G.R., Chen, H., Sharma, H.C., Chandel, A.K and Gao, B., 2021. Nanoparticles and their impacts on seed germination. In Plant Responses to Nanomaterials: Recent Interventions, and Physiological and Biochemical Responses (21- 31). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Albanese, A., Tang, P.S. and Chan, W.C. (2012). The effect of nanoparticle size, shape and surface chemistry on biological systems. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering. 14: 1-16.

Avellan, A., Schwab, F., Masion, A., Chaurand, P., Borschneck, D., Vidal, V., Rose, J., Santaella, C and Levard, C., 2017. Nanoparticle uptake in plants: gold nanomaterial localized in roots of Arabidopsis thaliana by X-ray computed nanotomography and hyperspectral imaging. Environmental Science &

Technology. 51(15). 8682-8691.

Avellan, A., Morais, B.P., Miranda, M., Dias, D.S., Lowry, G.V. and Rodrigues, S.M. (2021). Hydrophobic interactions at the phylloplane modulating adhesion, uptake and in planta fate of foliarly deposited particles. Goldschmidt 2021• Virtual• 4-9 July.

Deng, Y.Q., White, J.C and Xing, B.S. 2014. Interactions between engineered nanomaterials and agricultural crops: implications for food safety. Journal of Zhejiang University Science A. 15(8): 552-572.

Honour, S.L., Bell, J.N.B., Ashenden, T.W., Cape, J.N and Power, S.A. (2009). Responses of herbaceous plants to urban air pollution: effects on growth, phenology and leaf surface characteristics. Environmental Pollution. 157(4): 1279-1286.

Ibrahim, K.S. 2013. Carbon nanotubes-properties and applications: a review. Carbon letters. 14(3): 131-144.

Jeevanandam, J., Barhoum, A., Chan, Y.S., Dufresne, A and Danquah, M.K. 2018. Review on nanoparticles and nanostructured materials: History, sources, toxicity and regulations. Journal of Nanotechnology. 9: 1050-1074.

Kumari, M., Ernest, V., Mukherjee, Aand Chandrasekaran, N., 2012. In vivo nanotoxicity assays in plant models. In Nanotoxicity: Methods and Protocols ( 399-410). Totowa, NJ: Humana Press.

Moore M. 2006. Do nanoparticles present ecotoxicological risks for the health of the aquatic environment? Environ Int. 32:967–976.

Mahakham, W., Sarmah, A.K., Maensiri, S. et al. 2017. Nanopriming technology for enhancing germination and starch metabolism of aged rice seeds using phytosynthesized silver nanoparticles. Sci Rep 7, 8263. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-08669-5

Nel, A., Xia, T., Mädler, L and Li, N. 2006. Toxic potential of materials at the nanolevel. Science. 311(5761): 622-627.

Qian, H., Peng, X., Han, X., Ren, J., Sun, L and Fu, 2013. Comparison of the toxicity of silver nanoparticles and silver ions on the growth of terrestrial plant model Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Environmental Sciences. 25(9): 1947- 1956.

Roco, M. 2003. Broader societal issues of nanotechnology. Journal of Nanoparticle Research. 5:181-189.

Roduner, E. 2006. Size matters: Why nanomaterials are different. Chemical Society Reviews. 35: 583–592.

Siddaiah, C.N., Prasanth, K.V.H., Satyanarayana, N.R., Mudili, V., Gupta, V.K., Kalagatur,N.K., Satyavati, T., Dai, X.-F., Chen, J.-Y.,Mocan, A., Singh, B.P.,

Srivastava, R.K. 2018. Chitosan nanoparticles having higher degree of acetylation induce resistance against pearl millet downy mildew through nitric oxide generation. Sci. Rep. 8, 2485.

Singla, R., Kumari, A and Yadav, S.K. 2019. Impact of Nanomaterials on Plant Physiology and Functions. In Nanomaterials and Plant Potential. Springer, Cham. 349-377.

Thiruvengadam, M., Chi, H.Y and Kim, S.H., 2024. Impact of nanopollution on plant growth, photosynthesis, toxicity, and metabolism in the agricultural sector: An updated review. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 207. 108370.

Zhu, H and Njuguna, J. 2014. Nanolayered silicates/clay minerals: uses and effects on health. In Health and Environmental Safety of Nanomaterials. Woodhead Publishing. 133-146.

- Effect of Sowing Window on Nodulation, Yield and Post – Harvest Soil Nutrient Status Under Varied Crop Geometries in Short Duration Pigeonpea (Cajanus Cajan L.)

- Nanotechnology and Its Role in Seed Technology

- Challenges Faced by Agri Startups in Andhra Pradesh

- Constraints of Chcs as Perceived by Farmers in Kurnool District of Andhra Pradesh

- Growth, Yield Attributes and Yield of Fingermillet (Eleusine Coracana L. Gaertn.) as Influenced by Different Levels of Fertilizers and Liquid Biofertilizers

- Consumers’ Buying Behaviour Towards Organic Foods in Retail Outlets of Ananthapuramu City, Andhra Pradesh